- 22 Jan 2026

- Loïc Roux

Designing Therapeutic Oligonucleotides – A Practical Framework from Biology to Sequence Selection

Therapeutic Oligonucleotide Design: A Practical Framework

By Dr Loïc Roux, Technical Director of New Modalities – Drug Discovery

Abstract

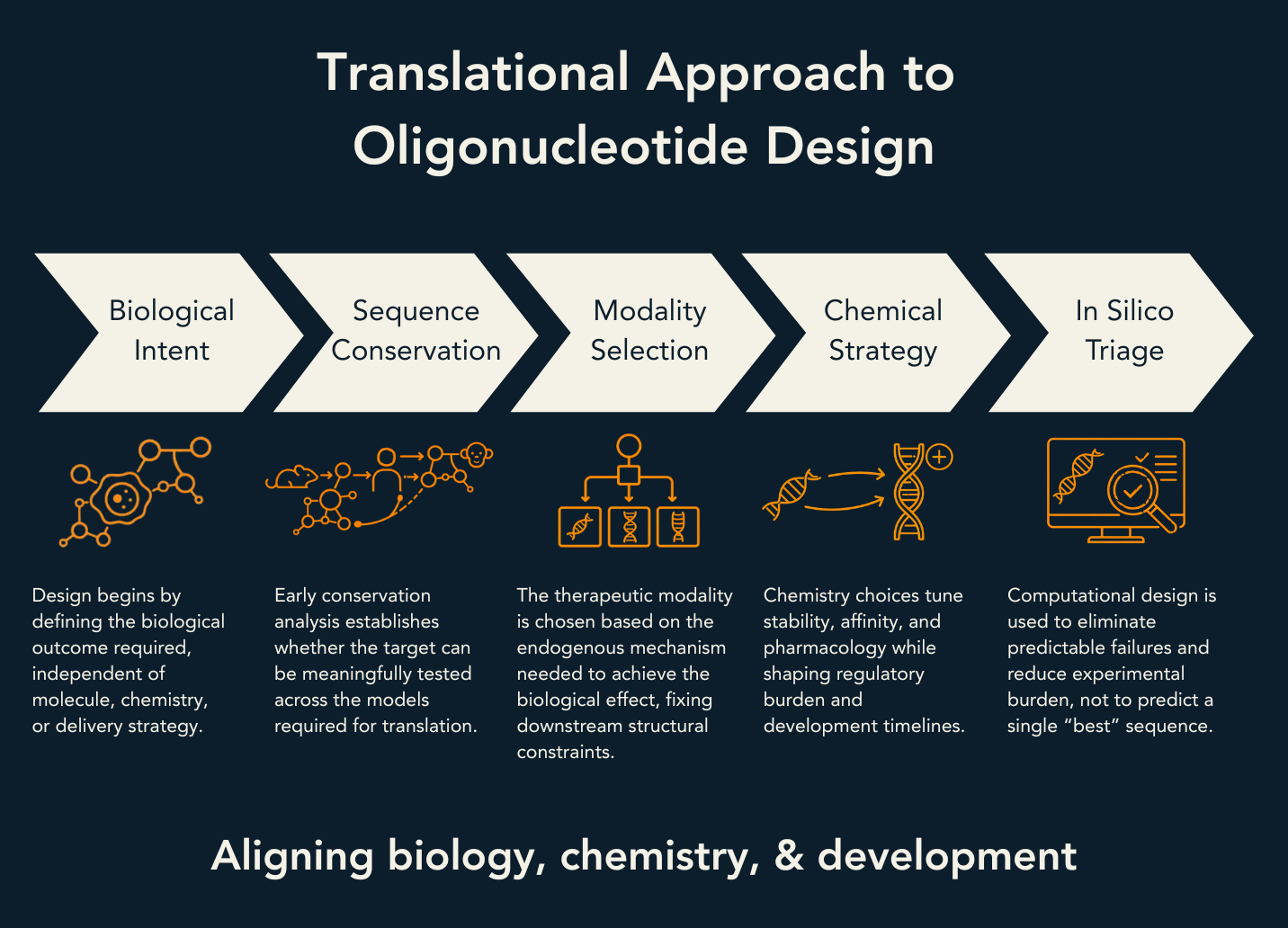

Therapeutic oligonucleotides enable precise modulation of gene expression by harnessing endogenous nucleic-acid–based regulatory mechanisms. However, successful molecules are not obtained by sequence complementarity alone. The choice of modality determines the biological machinery responsible for the therapeutic effect and imposes strict structural, chemical, and regulatory constraints that must be considered from the earliest design stages.

This article presents a mechanism-first framework for therapeutic oligonucleotide design. It begins with biological intent, integrates sequence conservation and model strategy as early feasibility gates, selects the appropriate modality, translates that choice into chemistry and positional rules, and finally applies in-silico sequence triage to reduce experimental burden while controlling off-target risk. The focus is on sequence and chemistry design; delivery is discussed only where it is inseparable from chemistry choice.

Introduction: Natural Regulatory Mechanisms, Chemistry Choices, and the Critical Path

Cells have long relied on nucleic acids to regulate nucleic acids. RNA interference, antisense-mediated RNA processing, and CRISPR-based adaptive immunity evolved as endogenous control systems, not as pharmacological targets. Their discovery transformed therapeutic thinking by revealing that gene expression could be modulated through sequence-programmed recognition, rather than through classical ligand–receptor interactions (Fire et al., 1998; Elbashir et al., 2001).

A defining characteristic of oligonucleotide therapeutics is that the molecule itself rarely performs the biological action. Instead, it acts as a molecular instruction, redirecting existing cellular machinery. This makes oligonucleotide design both powerful and unforgiving: sequence complementarity is necessary but never sufficient. If a molecule does not adopt the correct structure or chemistry required by the pathway it aims to engage, it will fail regardless of binding strength.

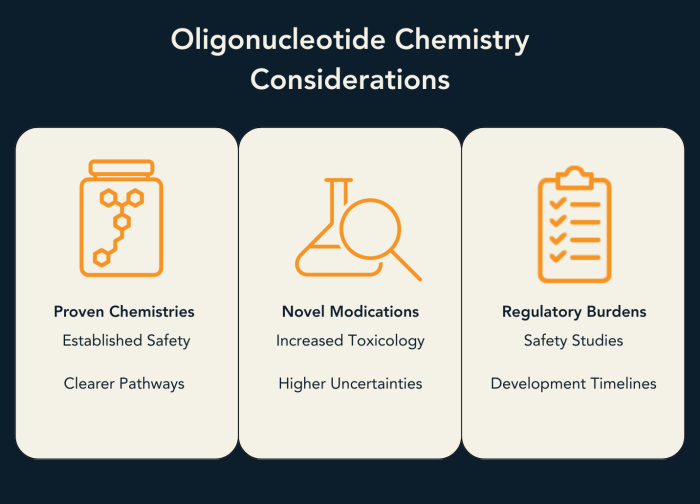

Crucially, chemistry choice in oligonucleotide design carries implications far beyond potency or stability. Unlike small molecules, oligonucleotide chemistries occupy a relatively small but deeply characterised chemical space. Some modification families have extensive clinical and regulatory precedent, while others remain experimental or platform-defining (Bennett & Swayze, 2010; Khvorova & Watts, 2017).

As a result, chemistry selection directly influences preclinical burden, regulatory expectations, and speed to clinic. Chemistries used in approved drugs or late-stage clinical programmes benefit from established toxicology understanding and clearer regulatory pathways. In contrast, introducing novel or sparsely characterised modifications typically requires expanded nonclinical safety packages, deeper metabolite profiling, and increased uncertainty during early development (Roberts et al., 2020).

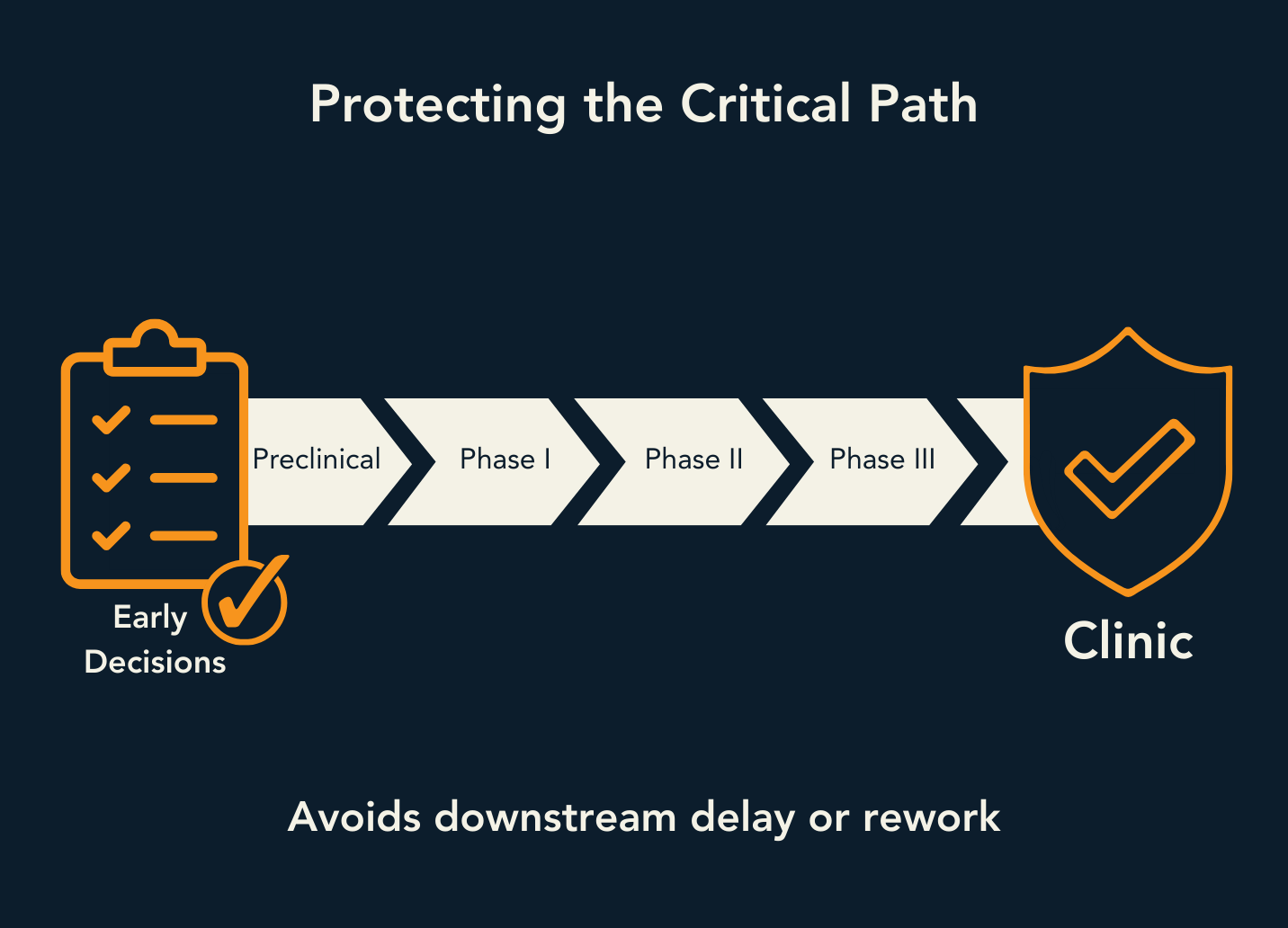

This does not argue against innovation. Rather, it reflects a fundamental reality: chemistry choice is a strategic decision that defines the programme’s critical path from the outset. Effective oligonucleotide design therefore integrates biology, modality, chemistry, model strategy, and development considerations from the very first design decisions.

Why this Matters for Founders and Investors

For founders and investors, oligonucleotide programmes rarely fail because the biology was wrong or the sequence was imperfect. They fail because early design decisions silently lock the programme onto an unfundable or slow critical path.

Choosing a modality before defining the biological outcome, optimising chemistry without considering regulatory precedent, or over-relying on in-silico rankings can create hidden risk that only surfaces after significant capital has been spent. In RNA therapeutics, chemistry is not merely a performance variable — it defines development burden, timelines, and regulatory confidence.

Programmes that align biology, modality, chemistry, and model strategy from the outset preserve optionality. They generate data that investors can trust, regulators can interpret, and partners can diligence efficiently. In practice, this is often the difference between a technically interesting asset and a platform that can scale into a credible company.

Start With the Biological Question, Not the Molecule

Effective oligonucleotide design does not begin with chemistry, sequence length, or software tools. It begins with a clear definition of what must change in biology.

The same gene can require very different therapeutic strategies depending on the desired outcome. In some cases, permanent modification of the genome is appropriate; in others, transient and reversible modulation is safer and sufficient. Some diseases require reduction of RNA abundance, while others demand preservation of the transcript with altered processing. Even the subcellular location of the target RNA—nuclear versus cytoplasmic—can determine whether a given modality is viable.

These distinctions are not semantic. They define which endogenous mechanism must be engaged, and therefore which molecular architectures are even possible.

Framing the problem at the level of biological intent prevents a common failure mode in oligonucleotide development: optimising sequence and chemistry for a mechanism that is fundamentally misaligned with the therapeutic goal.

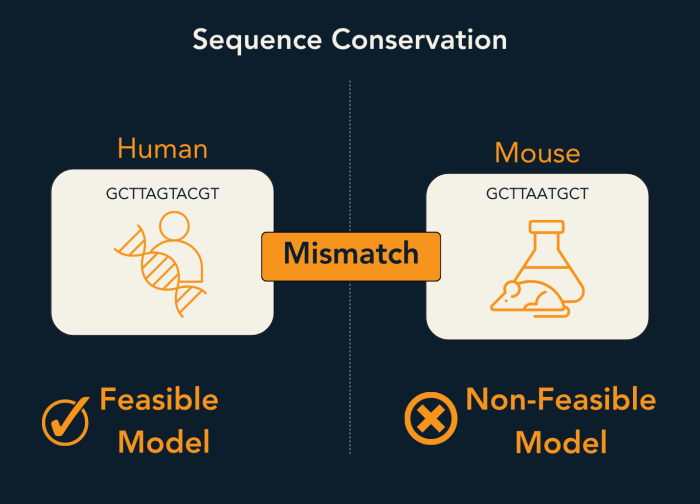

Sequence Conservation, Model Strategy, and the Critical Path

Once the biological objective is defined, experienced teams immediately ask a second question—one that is often underestimated in early design discussions:

In which biological systems must this hypothesis be tested?

For oligonucleotide therapeutics, this question cannot be postponed. Because these molecules are sequence-defined, even minor species differences can eliminate activity entirely. A single mismatch, a shifted exon boundary, or a divergent regulatory element may be sufficient to prevent binding or alter mechanism.

As a result, sequence conservation is a design constraint rather than a development detail. Unlike small molecules or antibodies, oligonucleotides do not tolerate sequence drift. If a target region is not conserved between human and the intended preclinical model, efficacy data may be uninterpretable regardless of in vitro performance.

For this reason, conservation analysis is introduced early—not to optimise sequences, but to define what is feasible to test on the critical path. In many programmes, this step dramatically reduces the design space, but it prevents far more costly failures later in development.

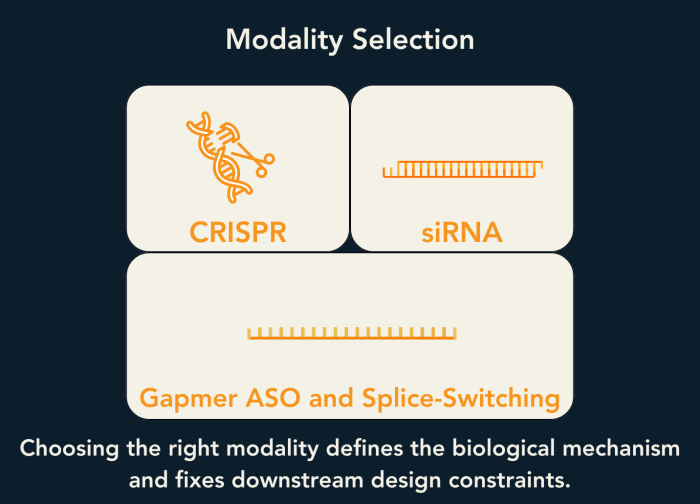

Choosing the Right Modality: A Mechanism-First Framework

With biological intent and feasibility constraints defined, modality selection follows logically.

CRISPR technologies enable permanent genomic modification and are suited to indications where irreversible change is required (Hendel et al., 2015). siRNAs reduce RNA abundance via Argonaute-mediated cleavage within the RNA interference pathway (Elbashir et al., 2001). RNase H gapmer antisense oligonucleotides degrade RNA through recognition of DNA/RNA heteroduplexes (Nowotny et al., 2005). Steric blockers and splice-switching oligonucleotides modulate RNA processing without inducing degradation (Havens & Hastings, 2016).

Selecting a modality is equivalent to selecting the protein machinery—or deliberate absence thereof—that will execute the therapeutic effect. This choice defines all downstream structural and chemical constraints.

Structural and Chemical Requirements by Modality

Although all oligonucleotides rely on base pairing, not all base-paired structures are biologically equivalent. Each modality imposes architectural rules dictated by its protein of action.

siRNA: A-form RNA Geometry and Position-Specific Chemistry

siRNAs exploit the RNA interference pathway, which evolved to process RNA substrates. Productive RISC activity requires the guide strand to maintain RNA-like A-form geometry compatible with Argonaute binding and catalysis (Wang et al., 2009).

This explains why siRNA chemistry is position-specific rather than uniform. The seed region (guide positions 2–8) drives target recognition and miRNA-like off-target effects. A single 2′-O-methyl modification at guide position 2 has been shown to significantly reduce off-target silencing while preserving on-target activity (Jackson et al., 2006).

Some positions are effectively locked by mechanism. Guide position 14, located near the catalytic centre, is particularly sensitive; modification at this position can abolish silencing by disrupting Ago2-mediated cleavage (Zheng et al., 2013).

Historically, 2′-fluoro substitutions were widely used to enhance stability while preserving RNA geometry. As clinical experience accumulated, designs increasingly balanced fluorine density against off-target and safety considerations, leading to reduced 2′-F usage in modern architectures (Khvorova & Watts, 2017).

The passenger strand tolerates heavier modification and is exploited as a chemical lever to bias strand selection and reduce unintended loading.

RNase H Gapmer ASOs: DNA–RNA Heteroduplex Rules

RNase H gapmer ASOs rely on a strict substrate requirement: a DNA/RNA heteroduplex. RNase H does not act on RNA/RNA duplexes, as shown by structural studies of human RNase H1 bound to hybrid substrates (Nowotny et al., 2005; Nowotny et al., 2007).

This imposes a non-negotiable architectural rule: a contiguous DNA gap must be preserved. Chemical freedom exists in the wings, where high-affinity chemistries such as MOE or LNA/cEt increase binding strength and stability without disrupting RNase H recruitment (Koshkin et al., 1998; Straarup et al., 2010).

Higher affinity enables shorter ASOs, which can reduce partial off-target hybridisation and improve developability. However, excessive affinity can increase RNase H-mediated off-target cleavage, making length and melting temperature critical design knobs rather than optimisation endpoints (Lima et al., 2007).

Steric Blockers: From Charged DNA to Mechanism-Pure Chemistries

Steric blockers bind RNA to physically block protein interactions rather than recruit nucleases. Early blocker strategies relied on charged DNA oligonucleotides, often phosphorothioate-modified. While accessible, these molecules frequently recruited RNase H, leading to unintended RNA degradation and mechanistic ambiguity.

The field therefore moved to fully modified RNA analogues, most notably 2′-O-methyl and MOE, which increased affinity and nuclease resistance while eliminating RNase H recruitment. This shift enabled mechanism-pure splice switching, where occupancy—not cleavage—drives the therapeutic effect (Havens & Hastings, 2016).

Neutral backbones such as PMO and PNA represent a further refinement. These chemistries are structurally distinct and largely invisible to nucleic-acid-processing enzymes, conferring exceptional stability and clean mechanism (Summerton & Weller, 1997; Summerton, 1999). PMO-based therapies have demonstrated long tissue persistence and sustained pharmacodynamic effects in vivo (Wu et al., 2011).

The trade-off is delivery: neutral backbones exhibit poor spontaneous cellular uptake and are frequently conjugated to peptides or other delivery enhancers (Roberts et al., 2020).

CRISPR Guide RNAs: Chemistry Within RNP Constraints

CRISPR guide RNAs function within a Cas ribonucleoprotein complex, imposing strict structural requirements. Chemistry is best applied to terminal positions to protect against exonucleases while preserving internal RNA geometry. Excessive internal modification is often poorly tolerated (Hendel et al., 2015).

As a result, CRISPR design remains dominated by sequence specificity, with chemistry used primarily to support stability and handling.

Chemistry as a Design, Development, and Regulatory Decision

Once a modality has been selected and its structural constraints are understood, chemistry becomes the main lever for tuning how an oligonucleotide behaves. It is tempting to treat chemical modification as a purely technical optimisation. In practice, chemistry choices shape not only molecular performance, but also regulatory burden, interpretability, and development speed.

The reason is simple: oligonucleotide therapeutics sit within a relatively small, deeply characterised chemical space, where regulators and the field increasingly think in terms of chemistry families (e.g., phosphorothioates, 2′-OMe/2′-F RNA sugars, MOE wings, LNA/cEt, PMO). Reviews of the field consistently highlight that the success of modern oligonucleotide drugs is inseparable from the emergence of these repeatable chemistry platforms (Bennett & Swayze, 2010; Khvorova & Watts, 2017).

This has immediate consequences for development strategy. Chemistries with extensive precedent—especially those used across multiple clinical programmes—benefit from an implicit body of knowledge: expected PK/PD behaviour, common class liabilities, and established expectations for nonclinical packages. That does not mean regulators “approve chemistries,” but it does mean that familiar chemical classes generally reduce uncertainty during translation, because risk is better bounded.

In contrast, introducing a novel or sparsely characterised chemistry often shifts the entire programme’s critical path. Even when the modification is mechanistically attractive, it can trigger additional workstreams: expanded toxicology, deeper metabolite/degradation profiling, and more conservative early development assumptions. This is why platform and regulatory considerations are frequently discussed alongside potency and specificity in modern oligonucleotide development reviews (Kanasty et al., 2012; Khvorova & Watts, 2017).

This isn’t an argument against innovation. It’s an argument for making the trade-off explicit early. If speed to clinic is a priority, teams often converge on well-precedented chemistries. If long-term differentiation is the priority, teams may accept a heavier early burden to establish a new chemical platform.

Either way, chemistry is not a late-stage optimisation. It is a strategic design decision that shapes timelines, risk, and interpretability from the outset.

From Target Definition to Experimental Testing: The Full Sequence Design Workflow

With biological intent, conservation constraints, modality choice, and chemistry direction in place, sequence design enters its most operational phase. Here, a large theoretical design space is reduced—systematically and defensibly—into a small set of compounds worth synthesising and testing.

A core principle matters here: In silico design is a triage process, not a prediction engine.

In other words, the goal is rarely to pick one “best” oligo on a screen. The goal is to remove candidates that are likely to fail for known reasons, while preserving enough diversity that early experiments are informative.

Generate the Candidate Space First (Before Filtering)

Sequence selection does not begin with ranking; it begins with defining the space of sequences that could plausibly work. This distinction matters, because all subsequent filtering and scoring steps operate on the candidate set that is generated at this stage.

In practice, candidate sequences are generated by systematically scanning the target RNA while enforcing modality-specific architectural rules. For siRNA and antisense oligonucleotides, this typically involves sliding a window across the transcript to generate all possible sequences of the required length. For RNase H gapmers, generation already enforces the presence of a contiguous DNA gap, reflecting the strict requirement for a DNA/RNA heteroduplex (Nowotny et al., 2005). For splice-switching steric blockers, generation is often restricted to functionally relevant regions such as splice junctions and regulatory elements, where position frequently dominates outcome (Havens & Hastings, 2016). For CRISPR, candidate guides are generated by scanning for PAM-compatible sites, with established frameworks used to enrich for active guides and manage off-target risk (Doench et al., 2016).

This step is worth stating explicitly: downstream optimisation, scoring, and risk filters can only act on the sequences that are generated here. A poorly defined candidate space cannot be rescued by even the most sophisticated in silico triage.

Apply Feasibility Gates Before Optimisation

Before any attempt is made to score or optimise “good” sequences, experienced teams apply feasibility gates that reflect the realities of the programme’s critical path. At this stage, the question is not which sequences look best in silico, but which sequences can be meaningfully tested, interpreted, and progressed.

In practice, this means removing candidates that violate fixed architectural or chemistry constraints imposed by the chosen modality—for example, preserving a contiguous DNA gap for RNase H recruitment, or respecting known positional tolerances in siRNA designs. Equally important, sequences that are not conserved in the species required for in vivo translation are removed early if the model strategy depends on them.

This gate is where model strategy stops being a planning slide and becomes a hard design constraint. Sequences that cannot generate interpretable data in the relevant biological system are excluded without regret, even if they appear attractive by conventional design metrics. Applying these feasibility filters early often reduces the candidate pool substantially, but it prevents far more costly re-design and re-interpretation later in development.

Universal First-Pass Filters (Manufacturability, Safety Flags, Obvious Off-Targets)

Once feasibility is established, teams apply universal first-pass filters to remove candidates that are likely to fail for predictable, non-biological reasons. These filters are not about fine optimisation; they are about protecting throughput and avoiding failure modes that add cost without generating insight.

Some of these criteria are deliberately pragmatic. Extremes of GC content, long homopolymers, repetitive motifs, or strong self-complementarity can create synthesis, purification, solubility, or handling issues. While these features do not guarantee failure, excluding obvious liabilities early prevents wasted experimental cycles and preserves development efficiency.

In parallel, many pipelines screen out sequence motifs associated with innate immune activation. The biological response to siRNA and related constructs—and the fact that immunogenicity can be influenced by sequence, chemistry, and formulation—has been extensively discussed (Kanasty et al., 2012). No filter guarantees immunological silence, but removing known risk motifs is a sensible risk-reduction step when alternative sequences exist.

Finally, candidates are aligned transcriptome-wide to eliminate perfect matches and the most obvious high-risk near matches. At this stage, the objective is rapid elimination of clearly unsafe candidates, not exhaustive off-target prediction. Deeper off-target analysis is reserved for later stages, once the candidate set has been reduced to a manageable and biologically relevant panel.

Target Structure and Accessibility: Avoiding Predictable Losers

RNA targets are not linear strings of nucleotides. They are folded, dynamic molecules that are frequently associated with proteins, and not all complementary sites are equally accessible in a cellular context. This reality matters most for modalities that rely on sustained binding, such as RNase H gapmers and steric blockers.

As a result, structure-aware design is best used as a tool to avoid predictable failures rather than to identify guaranteed winners. In practice, regions that are deeply embedded in stable secondary structures or likely to be persistently protein-bound are deprioritised, while loops, junctions, and exon–intron boundaries are enriched because they are more likely to be physically accessible.

This distinction is important. Overinterpreting RNA structure predictions can create false confidence, while ignoring structure entirely leads to repeated selection of sites that consistently underperform. Used with restraint, accessibility analysis improves the odds that early experiments test meaningful hypotheses rather than predictable losers.

Modality-Specific Triage: Potency Enrichment and Risk Control

After universal filtering, modality-specific logic becomes dominant. Although the molecular details differ, modality-specific triage follows the same underlying logic across oligonucleotide classes. At this stage, selection shifts from general feasibility to mechanism-specific risk management. The objective is no longer to maximise theoretical potency, but to enrich for candidates that are most likely to produce interpretable, translatable biology given the constraints of each pathway.

For siRNA

siRNA design balances potency with the risk of miRNA-like off-target effects. Classical siRNA design rules and scoring frameworks exist (Reynolds et al., 2004; Ui-Tei et al., 2004), but modern practice often combines these with explicit off-target mitigation strategies.

A landmark example is the sharp position dependence of off-target reduction by a single 2′-O-methyl at guide position 2, which reduces seed-mediated off-target transcript silencing (Jackson et al., 2006).

Equally important, some positions are mechanistically constrained: modification at guide position 14 can abolish silencing by reducing RISC loading and target degradation (Zheng et al., 2013).

As a result, experienced teams rarely select just one siRNA; they select a small panel spanning different transcript regions and seed properties.

For RNase H Gapmers

Gapmer triage prioritises accessible regions, manages affinity (length and Tm), and screens for near matches capable of forming RNase H-competent heteroduplexes. The central constraint—RNase H recognition of RNA/DNA hybrids—is supported by structural work demonstrating substrate recognition features (Nowotny et al., 2005).

For Steric Blockers / Splice Switching

For steric blockers, position is often more important than “best binder.” Designs are therefore driven by functional annotation of splice junctions and regulatory elements, not only by thermodynamic ranking (Havens & Hastings, 2016).

When neutral chemistries such as PMO are used, long stability and enzymatic invisibility are advantages, but uptake can become limiting; long-term PMO dosing and persistence have been explored in vivo (Wu et al., 2011).

For CRISPR Guide RNAs

For CRISPR, candidate selection is largely risk management: PAM context, on-target activity enrichment, and genome-wide off-target enumeration. Widely used guide design frameworks were developed from large-scale datasets (Doench et al., 2016).

Across modalities, the common theme is that triage is driven by mechanism-specific failure modes rather than by abstract ranking scores — and this is why early experimental panels are deliberately diverse rather than optimised to a single “best” design.

Efficacy Prediction Models: Enrichment, Not Authority

Across modalities, prediction models are valuable tools, but they are not decision engines. Their strength lies in enriching for more promising candidates and removing obvious weak designs—not in identifying a single “best” sequence with confidence.

This is consistent with how the field uses classical siRNA activity rules (Reynolds et al., 2004; Ui-Tei et al., 2004) and modern CRISPR guide scoring frameworks (Doench et al., 2016). In practice, these models improve average outcomes across a candidate set, but they do not replace experimental validation or biological judgement.

Treating prediction scores as authoritative can create false confidence and narrow experimental panels prematurely. Used appropriately, these tools reduce noise and experimental burden while preserving the diversity needed for early studies to be informative rather than confirmatory.

From Ranked Lists to Experiments

The output of a well-designed in silico workflow is rarely a single “winner.” Instead, it is a ranked and annotated list that supports informed experimental choice. Most experienced teams select a deliberately diverse panel of candidates—often on the order of 5–30 sequences—because early studies are intended to generate insight, not just confirm predictions.

Diversity at this stage is intentional. Testing sequences that span different target regions, sequence features, and mechanistic sensitivities allows programmes to learn which constraints matter most in their specific biological context. This information is often more valuable than identifying a single highly active construct early.

This transition—from ranked lists to experiments—is where good design becomes good science. The goal is not to validate an algorithm, but to maximise information gain while preserving the translational critical path.

Conclusion: Design as Protection of the Critical Path

Therapeutic oligonucleotide design is often presented as a problem of sequence optimisation. In practice, it is a problem of decision ordering.

Most failures do not arise because the “wrong” sequence was chosen, but because early design decisions quietly constrained what could be tested, interpreted, and progressed.

Across modalities, the same pattern emerges. Starting from biological intent ensures that the correct endogenous mechanism is engaged. Introducing conservation and model strategy early prevents dead ends where promising human sequences cannot be evaluated meaningfully in vivo. Selecting a modality fixes the protein machinery—or deliberate absence thereof—that will execute the therapeutic effect and defines the structural rules the molecule must obey. Chemistry then becomes both a molecular and a strategic choice, shaping not only potency and stability, but also regulatory expectations, preclinical burden, and speed to clinic.

Within this framework, in silico sequence design plays a specific and disciplined role. It is not a substitute for biology, nor a guarantee of success. Its value lies in systematically eliminating predictable failures, reducing experimental burden, and enabling early studies to be informative rather than confirmatory. Used well, it accelerates learning. Used poorly, it creates false confidence.

As oligonucleotide therapeutics continue to mature as a drug class, success increasingly depends on integrating mechanistic understanding, chemical realism, and development strategy from the very first design step. The objective is not to identify a single “perfect” molecule in silico, but to build a workflow that preserves optionality, generates interpretable data, and supports confident progression.

In that sense, effective therapeutic oligonucleotide design is less about writing the perfect sequence. It’s about protecting the critical path from day one.

References

- Fire, A., Xu, S., Montgomery, M. K., Kostas, S. A., Driver, S. E., & Mello, C. C.

Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans.

Nature. 1998;391:806–811. - Elbashir, S. M., Lendeckel, W., & Tuschl, T.

RNA interference is mediated by 21- and 22-nucleotide RNAs.

Genes & Development. 2001;15:188–200. - Reynolds, A., Leake, D., Boese, Q., Scaringe, S., Marshall, W. S., & Khvorova, A.

Rational siRNA design for RNA interference.

Nature Biotechnology. 2004;22:326–330. - Ui-Tei, K., Naito, Y., Takahashi, F., et al.

Guidelines for the selection of highly effective siRNA sequences for mammalian and chick RNA interference.

Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;32:936–948. - Jackson, A. L., Burchard, J., Schelter, J., et al.

Position-specific chemical modification of siRNAs reduces off-target transcript silencing.

RNA. 2006;12:1197–1205. - Wang, Y., Sheng, G., Juranek, S., Tuschl, T., & Patel, D. J.

Structure of the guide-strand-containing Argonaute silencing complex.

Nature. 2009;456:209–213. - Zheng, J., Mou, H., Cho, Y., et al.

A single modification at position 14 of the siRNA guide strand abolishes its gene-silencing activity.

FASEB Journal. 2013;27:1–12. - Nowotny, M., Gaidamakov, S. A., Crouch, R. J., & Yang, W.

Crystal structures of RNase H bound to an RNA/DNA hybrid: substrate specificity and metal-dependent catalysis.

Cell. 2005;121:1005–1016. - Lima, W. F., Wu, H., Nichols, J. G., et al.

Human RNase H1 discriminates between subtle variations in the structure of the heteroduplex substrate.

Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282:27168–27178. - Koshkin, A. A., Singh, S. K., Nielsen, P., et al.

LNA (locked nucleic acid): synthesis and properties.

Tetrahedron. 1998;54:3607–3630. - Straarup, E. M., Fisker, N., Hedtjärn, M., et al.

Short locked nucleic acid antisense oligonucleotides potently reduce apolipoprotein B.

Nucleic Acids Research. 2010;38:7100–7111. - Summerton, J., & Weller, D.

Morpholino antisense oligomers: design, preparation, and properties.

Antisense & Nucleic Acid Drug Development. 1997;7:187–195. - Summerton, J.

Morpholino antisense oligomers: the case for an RNase H-independent structural type.

Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1999;1489:141–158. - Havens, M. A., & Hastings, M. L.

Splice-switching antisense oligonucleotides as therapeutic drugs.

Nucleic Acids Research. 2016;44:6549–6563. - Wu, B., Li, Y., Morcos, P. A., et al.

Long-term rescue of dystrophic muscle function by antisense oligonucleotides.

Molecular Therapy. 2011;19:1149–1158. - Hendel, A., Bak, R. O., Clark, J. T., et al.

Chemically modified guide RNAs enhance CRISPR-Cas genome editing in human primary cells.

Nature Biotechnology. 2015;33:985–989. - Doench, J. G., Fusi, N., Sullender, M., et al.

Optimized sgRNA design to maximize activity and minimize off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9.

Nature Biotechnology. 2016;34:184–191. - Bennett, C. F., & Swayze, E. E.

RNA targeting therapeutics: molecular mechanisms of antisense oligonucleotides as a therapeutic platform.

Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2010;50:259–293. - Khvorova, A., & Watts, J. K.

The chemical evolution of oligonucleotide therapies of clinical utility.

Nature Biotechnology. 2017;35:238–248. - Kanasty, R. L., Whitehead, K. A., Vegas, A. J., & Anderson, D. G.

Action and reaction: the biological response to siRNA and its delivery vehicles.

Molecular Therapy. 2012;20:513–524. - Roberts, T. C., Langer, R., & Wood, M. J. A.

Advances in oligonucleotide drug delivery.

Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2020;19:673–694.